Tell me if this sounds familiar: “Don’t go to [XYZ neighborhood] at night. It’s a bad/rough neighborhood.”

It wouldn’t surprise me if everyone reading this has heard some permutation of this advice in their lifetime. As someone with a hobbyist perspective about linguistics, let me tell you the short version why I’ve stopped calling neighborhoods “good” or “bad,” and have instead elected to make the conscious decision to call them either “richer” or “poorer,” respectively: it’s because the language of racism is also subtle.

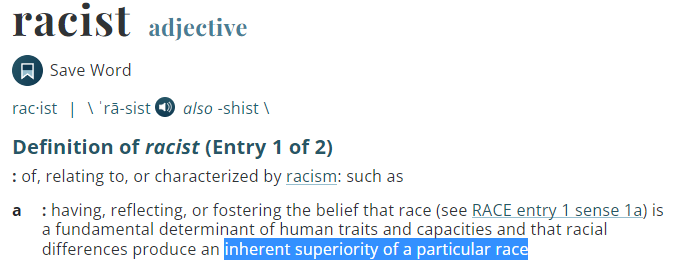

Yes, I am implying that calling a neighborhood “bad” is accidentally and incidentally racist. Some of you might have the knee-jerk reaction of rejecting the idea as “too sensitive” or “too woke.” Hear me out: I’m not calling you racist for calling a neighborhood “bad.” But that doesn’t mean you’re not susceptible to learned racist language. Remember that once, not long ago, the “n word” was just a way to describe Black people. Once, not long ago, it was normal to call women “broads.” Once, not long ago, it was considered appropriate to call all people of Asian descent “Orientals.” Just like we know better about those words now, I hope we can learn to be better about the language of today.

“Those are words that describe people, so of course they’re racist. How can calling a high-crime neighborhood “bad” be considered racist? Crime is bad. If the neighborhood is a high-crime neighborhood, it’s a bad neighborhood. That’s not racist.”

I presume the above logic is based on the idea that a “neighborhood” is not a person, and therefore does not have an ethnicity. While that may make sense on the surface, it’s a little more complicated than that when you drill down a bit.

A brief history of American economics and race

We don’t have to go back very far to realize that American economics has historically favored White people. Some counterpoints to this observation will insist that “everyone today has a fair and equal access to everything; it doesn’t matter what your race is.” Speaking strictly on paper, sure, there isn’t as much obviously racist legislation. In the 1950s–1960s, we had the Civil Rights Movement, punctuated by political figures in the Black community such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr…

…And everyone lived happily ever after.

…Just kidding.

I bring up the Civil Rights Movement because it happens to be the talking point that anti race-equity pundits point at and say, “See? We did it. We fixed the problem of legislative racism in America 70 years ago.” And while it’s true that we don’t have segregated water fountains, or “Whites only” pool hours, or “No Coloreds” diners, it’s a little disingenuous to call American politics “fixed.” Think of it this way: if you’re running in a relay race, and the other team happens to put your first runner in shackles from the start, of course your team will be behind the whole time. And that’s Critical Race Theory in America.

The effects of racist legislation have meant that people of color in America were historically prevented or denied access to a lot of the things that White America had from the very beginning, or haven’t you ever wondered why HOA suburbs are overwhelmingly White?

Put simply: White people have had first dibs on all the economic power since the beginning of the country. And if you’ve ever heard the saying “you gotta spend money to make money,” then it’ll make logical sense that if you don’t start with any money, it’s really fucking hard to make any money.

Here’s a question for you: of the top 10 richest people in America, how many do you think are White? Better yet, how far down the list do you think you have to go before you hit a non-White person? Even better, how far down the list until you hit a Black person? I’ll let you click that link and look for yourself. Spoiler alert: he’s definitely not in the top 100 (if you want to know his exact position, check the link after the conclusion).

Follow up question, why do you think that is? I won’t give you my opinion. But you should speculate for yourself.

Economics and crime (aka Mo’ money, less problems)

Now that we’ve discussed race and economics, let’s discuss economics and comfort. In the opening number of the musical Les Misérables, Jean Valjean is shown in chains, working as a slave to pay off a debt for stealing a loaf of bread.

Javert:

Follow to the letter your itinerary

This badge of shame

You shall show until you die

It warns you’re a dangerous man

Valjean:

I stole a loaf of bread!

My sister's child was close to death

And we were starving.

Javert:

You will starve again

Unless you learn the meaning of the law

Valjean:

Or the meaning of those 19 years

A slave of the law

If you’ve never been destitute, I’m sure you’ve never thought about stealing a meal to survive. When you go to the grocery store, do you haphazardly place whatever items you want in your cart without thinking about it much? Do you play the “guess the total” game when you approach the checkout line? Do you think about how many calories are in a box of plain spaghetti, and do the math on the spot to see if you can realistically hit 1500 calories in a day if you sit still and try to expend as little energy as possible while still being able to afford rent? Do you have a rent statement?

The closer you push someone towards the lower end of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the closer you push them towards desperation and a “do anything” type of will to survive.

“Just get a job! There are so many places hiring right now; it’s not that hard to survive.”

Sure, but when the only job that’ll hire you pays $10 an hour, after taxes, your take home pay is less than $400 a week. What happens when your rent is twice that, plus utilities? Not to mention the price of gas to fuel your car, which has a registration, insurance fee, and the cost of maintenance. And even if you eliminate the car, there’s the cost of everything else. The fact of the matter is that in America, escaping the cycle of poverty is fucking next to impossible. And just like generational wealth gets handed down, so does generational poverty. If it takes one person two jobs just to sustain themselves, while another person had the privilege of going to college while on their parents’ dime, that’s inherently not fair. I’m not saying the college grad needs to feel bad about themselves, but they should never claim it’s “easy” to do anything.

Whew, sorry, that got a little ranty. The point is that if you’re wealthy, odds are you’re comfortable. And if you’re poor, odds are it’s much harder to be comfortable. And when it’s a choice between stealing or starving, you bet your ass you’d steal to survive.

Economics and drugs

Picture this: you have no TV. No internet. You’re too hungry to have energy to play a sport. You’re cold because you’re living out of a car with an expired registration and no gas. You’re struggling to get a job because you don’t have a mailing address and you haven’t showered in a week. You’re fucking miserable. All you have is some scavenged leftovers and a few dollars you found in an old jacket pocket.

Then someone comes along with a way to make that misery just…go away.

Poverty is the biggest gateway to street drugs. And once you’re addicted to street drugs, your margins for getting out of poverty get extremely slim. And that’s pretty much all I have to say about that. It’s that simple, but it’s excruciatingly complicated at the same time. There’s a reason you don’t see a lot of heroin or crack in HOA suburbs, and it’s because they don’t need them to feel good or comfortable.

Economics, crime, drugs, and race

I want to take a moment to note that nowhere in the last two sections of this blog posting did I mention race. But if you happened to picture any specific demographic of person when I used any of the words above, there’s probably a reason for that. When I say “marginalized people,” what type of person do you think of? When I say “ghetto,” what type of person do you think of? Maybe you’re seeing a pattern by now. Here’s the one I see:

Rich = comfortable = less street drugs and street crime

Poor = uncomfortable = more street drugs and street crime

Note that I said “street drugs and street crime.” I’m aware that rich people do boutique drugs and engage in corporate crime (which—importantly—are both expensive). Also note that I still haven’t mentioned any race or ethnicity. But now I will:

Neighborhoods in metropolitan America are characteristically segregated by race/ethnicity. Not by modern legislation, mind you. But by the legacy of racist legislation that kept people of color marginalized into the slums and ghettos of America. This is why rich areas are mostly white, while poor areas are more ethnically diverse.

Back to square one

So a poor, high-crime, high-(street)-drug-use neighborhood is more likely to be populated by black and brown folks, while a rich, low-crime, low-(street)-drug-use neighborhood is more likely to be populated by White folks. That’s just a description of reality. But what’s the common denominator? Are Black and brown folks in these poor neighborhoods worse than their rich, White counterparts?

Are Black/brown folks bad and are White folks good?

That, my friends, is racist.

Conclusion:

If you truly believe that White folks and their neighborhoods aren’t better than people of color and their neighborhoods, then consider making the conscious decision to change your language around descriptions of those places. Honestly, even if you don’t think this idea has any merit, calling neighborhoods “richer” and “poorer” is frankly more accurate and paints a more nuanced, historically informed picture. Because being poor isn’t bad. But poverty incentivizes bad things. After all, money (and lack thereof, in many cases) is the root of all evil.

It just happens that generally, White people have more money than POC do.

Btw, as of this writing Robert F. Smith—an investor—is the first Black person to show up on the Forbes Top 400 Richest People list, sitting comfortably at position #141. The first non-white person is Jensen Huang (sitting at position #34), the CEO and president of Nvidia.